I was in my impressionable early twenties and attending a military course with 25 other officers at a prominent city in Western India when I experienced a puzzling situation that I still have not fully deciphered. Despite trying for 30 odd years.

It was on a quiet evening, when one of our extremely chivalrous course officers, Suneet ( name changed ) came rushing back to our quarters complaining loudly that his wife had been humiliated by the remarks of a civilian man while they were going around shopping.

Charged with righteous anger, and in a show of solidarity, many of us mooted getting onto motorbikes to ‘sort out’ the man. Some egged me to join, loudly advising that we should all wear helmets to conceal our identities. This was because if the Commandant got to know who we were, there would be hell to pay. I acquiesced on this “noble” mission and pillion-backed a comrade till we reached the offender who was walking in a semi-deserted lane. One by one, the roughly 12-13 in our gang slowed down, punched him and scooted away. When my turn came up, I took a close look at him. I saw a middle aged, portly, frightened man walking alone, carrying a shopping bag. I raised my fisted hand, but just could not bring it down on him. My bike rider didn’t wait for me and whisked us away safely back to our quarters. There, he and some others asked me – why didn’t I do it? I had no answer. I just hung my head down in confusion and some shame.

Over the years, I read many reports of similar incidents in military stations where young military officers even went to the extent of bashing up restaurants and causing a commotion in anger. Some reached the media, most did not. Some of the offenders were reprimanded, most let off. A recent one was in Tenga, Arunachal Pradesh five years ago, when no less than a commanding officer (CO) ordered his troops to ransack not just civilians, but a police station when he heard that one of his men had been slapped by a policeman in a restaurant. It caused such a furore that the ministers of defence and home had to descend in a day to restore the situation to normalcy. On national media, the CO openly stated that if anyone laid a finger on his men, they would face repercussions. Senior generals espressed solidarity with him while civil servants wrote acrimonious articles deriding the military’s behaviour.

These are a few isolated incidents no doubt. But why were they happening when, as I mulled over in my earlier piece Yes Loyalty. But to whom first? it should be obvious that our civilian, unarmed and physically weaker compatriots should be protected, not dominated by us military. Is there a deeper malaise hidden like an iceberg below the surface? Which may set off rapid and undesirable black jellyfish1 escalations in an untoward direction?

In India, like in most other countries, regimentation of valour starts in the early years. Young teens are drawn to military schools and mid-teens vie with lacs of others to be one of the few hundred ‘elite’ to be selected for the National Defence Academy (NDA). These select few are imbibed with British military ethics of integrity and physical courage, team spirit and solidarity, striving for excellence and abundant josh (enthusiasm). These no doubt are imperative qualities for soldiers to fight against all odds and achieve ‘victory’ as a team. And these are timeless and universal, stretching across all domains and cultures, whether it’s the submariners of the Western forces or the special forces in the Arab world or the fighter pilots of the Oriental countries.

But, over 75 years of independence from the British, many have noticed a melding in of Indian cultural values, some with merit, some not so much. And the original practices getting distorted and diluted incrementally over years and ever so minutely that they were undiscernable until a difficult situation made them suddenly appear starkly in the face.

The Suneet and Tenga incidents are apt examples of such situations. Solidarity in the British cultured NDA meant that one would never ‘let down’ a colleague by calling him out for the team’s failures. So if a team of Apaches ( cadets of ‘A’ squadron) lost a hockey match, they would accept collective responsibility for it no matter how much the Squadron Cadet Captain demanded to know which of the players messed up. And when a jersey was found missing from the gym, and everyone was rounded up to find the culprit, no one spoke up. So, the whole lot were punished for one person’s misdemeanor. This would lead to the culprit being ‘sorted out’ by his team mates subsequently and ‘reformed’ never to repeat the same.

But the factual and diluted version was that, the team mates never got to know who the culprit was because he never owned up to them. Which was against British ethos of accepting responsibility for ones actions. Worse still, he would not reform knowing he could get away with it and his team mates would keep ‘loyally’ taking the mass punishment without blinking an eye till the punisher tired of it. Loyalty meant ‘snitching’ ( complaining) about peers, superiors and subordinates was taboo. Even if it meant letting down the larger organisation.

In Suneet’s case, the afront of an officer’s lady-wife was enough to set a dozen military officers engrained in this distorted Western ethos to take drastic action against a meek compatriot without the slightest twinge of conscience. And unmindful of the damage it would cause their organisation and larger environment. In Tenga, it was the same, but sadly, here it was supported by senior generals who could one day, be at the top.

In military activity, valour gets easily combined ( or conflated) with organisational pride, loyalty and victory. The British cultivated the Naam-Namak-Nishaan ethos to meet their need to quell disputes, control their subjects and thus maintain peace within their empire. This Urdu-Hindi phrase literally translates to Name-Salt-Mark but is better understood as a metaphor for Organisational Pride-Loyalty to the employers-Unequalled Victory. This enabled them to use military units comprising of several hundreds of men to move and act in unison, like machines into battle, undeterred by why the people in front were their enemies or who they were protecting behind. After independence, this need diminished considerably and should have evolved into a relationship driven by the social contract - Where people paid the military to protect them and their resources against external aggression. But did this happen?

Let’s take a look at these events:

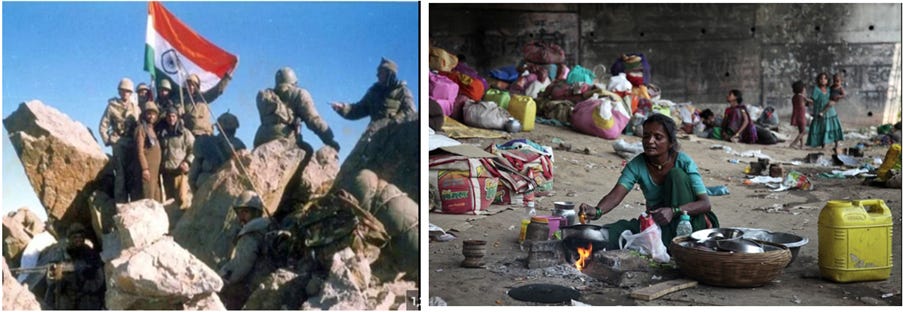

The proud landing at and capturing of Leh in Ladakh in 1947-48 by the military after Nehru ordered a ceasefire and approached the UN. When, there were no Pakistani or Chinese troops threatening Kashmir in that part of the region.

The proud capturing, in the 80s, of the icy Saltoro ridge, on the Western and Pakistani side of the agreed delimited line moving north of pt NJ9842 across the Siachen glacier. Were Pakistani mountaineers and military aiming and in a position to capture and maintain forces in the Southern Nubra valley? Using impossible logistics routes through the glacial territory lying in between?

The proudly massive mechanised-warfare based Ex Brasstacks in the mid 80s when India, five times stronger, practiced drills for attacking deep into Pakistan. Was Pakistan threatening India then? Did the Indian public want a military driven re-unification of Pakistan with India?

The proud launch into Sri-Lanka in the 80s. And from which we withdrew a few years later. If left unaddressed, would the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka have aimed at attacking India? And was India not in a position to protect the mainland from such an attack?

To be fair, barring the first, all of them received political sanction. Also, there were many justified operations in between. The 1961 war was triggered more by Indian actions, but once attacked, defending Indian territory was warranted. The 1962 liberation of Goa and 1971 liberation of Bangladesh were both necessary to meet the needs of the resident people. 1965 and 1999 were triggered by Pakistani insurgents into Kashmir and needed to be countered. The 2002 Op Parakram mobilisation was in response to the terrorist attack on the Parliament while the cross LC attacks in the mid 2010s were in response to terrorist actions.

But we also have the Doklam incident in 2017 where ground forces unnecessarily jumped across the international border resulting in an alienation from the world except Japan, the only country to have supported us. And then the Galwan incident where tensions drove our forces to unnecesarily cross over to the Chinese side, unannounced. These two incidents appear to be much like the Suneet one. Where the forces were driven by valour more than pragmatism.

But look at the economic burdens that each of the avoidable ones placed on the Indian people. Just one example of the massive cost of maintaining troops in Siachen is enough to understand the burden on the People of India. How much more was avoidable in the other instances? And try to visualise how the same money could have been spent in the perpetually underfunded areas of education and health care of the people. Would India have been saddled with 400 million poverty-trapped people, as it is today?

The colonial British never discussed the economic cost of military actions by Indian forces. Because it was ( I am guessing) all done in Britain. Is it possible that this is the reason that simple but important economic concepts of opportunity cost and sunk cost are never factored in decisions taken by the military? And valour takes prime and over-riding importance?

But getting back to valour and ethos, lets take a look at how our Indian cultural traditions and beliefs have influenced them. From small cultural changes like eating after the guests leave at regimental celebrations ( the British ate and drank with their guests) and wowing senior visitors with ever increasing hospitality ( athithi devo bhava or the ‘guest is god’), to transactional concepts of placing higher importance to personal ( and regimental) favours than organisational ( the Banya trader ethos) thereby defeating selflessness (nishkaam karma), loyalty to own regiments rather than the Army ( regimented casteism), deriding conscientious behaviour ( freedom to choose ones dharma in life) to pleasing and appeasing superiors ( bhakti), shunning reality (duniya sab maya hai) to an over-importance to outward visibility (dikhava).

But has this influence helped our Armed Forces to focus their efforts towards their primary role as given in Kautilyas Arthashastra? That of protecting the praja (people) ? Or do our forces still follow the British encultured aims of protecting, administering and even expanding our geographical, British demarcated, country? So that our valour can be demonstrated and our forces can continue to live in glory?

Do you see other angles which I have missed? Do share.

Black Jellyfish is a term used to represent events and phenomenon that have the potential of going postnormal by escalating rapidly.

There should be no doubt in anyone's mind (including the minds of the senior officers who defended the Tenga incident that taking the law into one's own hands is wrong. Should the Armed Forces officers or troops who do so in cases where there is a (perceived) wrong inflicted upon one of their comrades-in-arms be punished? Of course they should be penalized. No one would dispute that.

Does it damage the image of The Army? Probably yes ... but it probably also sometimes calls out the injustice of the law enforcement system. That is a nuanced question for which no generic answer can be provided. One on which a position can only be taken on a case-to-case basis.

Should they be severely punished in the same manner as the law deals with the common man?

Ah now that is a different question indeed!

The purpose of punishment under the law is two -fold:

(a) Punish the offender so that he doesn't repeat the offence.

(b) Serve as a deterrent from taking the law into their own hands for the general population.

Here the offenders in question are members of a highly disciplined and respected organization - the Indian Armed Forces. The offence has most likely not been perpetrated in any selfish cause but rather out of an (however misplaced) notion of organisational pride having been hurt. More often than not there is some significant provocation that has triggered the reaction.They aren't common criminals who would be emboldened to repeat the offence due to the lack of punishment. Lastly, they would most certainly be punished within the confines of a military milieu - probably more severely than the civilian penall code would do. The Tenga CO certainly wasn't let off scot-free. He had to face severe consequences. It is only in public that the senior officers stood up for him. So the first purpose of the penal code i.e. deterring the offender is adequately addressed even if the civilian police let's off the offenders with a light rap on the wrist.

Coming to the second purpose of penalty i.e. deterring the general populace from taking the law into their own hands, there is hardly any danger of that even if armed forces offenders aren't charged under the riot act. Everyone understands the special status of Armed Forces personnel and nary a civilian would imagine that he would be afforded the same leeway of being let off lightly offender is (in the public eye).

That is the reason why even senior police and civilian administration officers take a very different view of mob actions by armed forces personnel.

In no way am I condoning or encouraging such actions. They are wrong and there are no two ways about that. I was only speaking about the aftermath of such incidents.